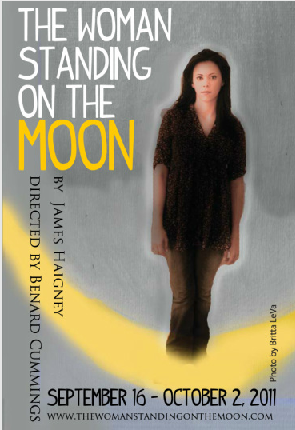

Attempting to grapple with the national ideological landscape of the present, James Haigney‘s new drama, The Woman Standing on the Moon, playing at United Stages on 30th Street, is undeniably ambitious. This is a serious minded engagement with the extremism of the times – religious and atheist. Set around Fayetteville, NC in 2006, the story focuses on the character of Mary Latrobe, a documentary filmmaker currently shooting a project examining Christian fundamentalism in the U.S. military. For her subject Mary has fastened on to a former Military Police officer, Randy Wallace, who is now a charismatic preacher in the area, with the glint of apocalypse in his eye. For Mary he is the ultimate bugaboo in the system, an evangelical extremist fashioning a corp elite of like-minded soldiers with a reach all the way up to the Pentagon. The mix is potentially, well, apocalyptic. She trains her camera relentlessly on Randy, willing him to expose his darker purpose, yet is met with a gentle-eyed, Bob Dylan quoting figure who espouses Christian wholesomeness and accord. We see clips of Randy’s camera self largely projected onto Christopher Thompson’s minimal, subtle set. He gives good face and sounds “harmlessly” idealistic. But Mary’s senses are sharp and she is not easily persuaded. Having both lost loved ones in acts of war, Mary and Randy are traumatized people. In their own ways they are looking to bring off some momentous coup that will bring life back into alignment; both are pushing for “revelation”. One deploys reason, the other, faith.

Complicating things for both of them are their personal, human lives. Mary has a damaged, alcoholic ex-husband, David (James Patrick Earley), and an attentive if somewhat callow young lover, Jack (Steven Michael Lang). Randy’s young pregnant wife, Belle, is a wide-eyed psychic with an unfettered manner and an aversion to violence. As the drama progresses, and the characters come to know each other, tensions build and the scene is set for, as Randy might say, just one spark to ignite the dry kindling of this world. In an extraordinary and surprising scene, with its own distinctive atmosphere, the spark, inevitably, is struck, and proves devastating for all the characters concerned. For all its broad examination of religious, social and cultural themes, it is simple grief, tended and untended, that is at the heart of this tale.

The use of film documentary is nicely incorporated throughout. In one scene we are presented initially with just rolling film footage as part of Randy’s faithful army community improvise a puppet show aimed at addressing bereavement for the children of army personnel. The show veers off course when the puppeteers, Sgt. Steve and Cpl. Pam, are incapable of maintaining the pretense required, as their own traumatic experiences languish unaddressed. The film stutters to a halt and the puppeteers emerge onto the stage to discuss the problem, a scene that is tellingly away from Mary’s recording camera. At once an incisive demonstration of the limitations of both documentary and fabrication, as well as a grotesquely comical episode, it features two of the most subtly disturbing glove puppets you may have cause to encounter.

Bernard Cummings directs the production with great fluidity, which is saying something given the number of scene changes, and the jarring emotional encounters between characters. Despite the tragic history she is trying to put behind her, there is a dismaying lack of vulnerability evident in Christa Kimlico Jones’s Mary. This may have more to do with the writing than with Jones’s performance, which is both concentrated and guarded. Even when she calls Jack in the middle of the night, having woken from a nightmare, before she has hung up, Haigney has her resume her tone of pragmatic, rational self-control. A woman who has been left, too often, to deal with everything on her own, she is hard to feel in this play. Haigney has a freer time with his characters Randy and Belle, and is well served by performances from, respectively, Taylor Flowers and, especially, Sarah Saunders. Scott O’Brien’s sound productions and Kevin R. Frech’s projections work well at fleshing out both story and atmosphere.

Like Mary’s camera, Haigney’s script is unrelenting and far-seeking. This is an intelligent investigation of large themes and a salutary depiction of how too frequently we can turn into the very thing we set out to counteract. The writing is dense and the allusions go deep. There is no final bulwark against the darkness (another of Randy’s phrases), only the possibility of insight and break-through. In the final scene we are left with the projection of a blue sky hanging over a vista of gently nodding wheat. Is it a clear, fresh horizon; amber waves of grain; or the fields of the Lord? The real question is, who is observing?

~~~

The Woman Standing on the Moon written by James Haigney, directed by Benard Cummings . Theatre at 30th Street Urban Stages 259 West 30th Street . September 15 – October 2 Tue-Sun 8pm . Click Here for tickets

{ 0 comments… add one now }