The Morningside Opera company offered up a quite singular interpretation of Pergolesi‘s Stabat Mater in their Fabulosa rendition on January 26th at Dixon Place, which proved, at once, a scholarly as well as a quite literal undressing of the original. Composed in 1736 – the year of Pergolesi’s death at the august age of 26 – the piece has been an iconic work in the canon of western sacred music ever since and has enjoyed an unbroken record of performance for nearly three hundred years. This surely says something about a work, to have endured so vigorously the vagaries of artistic, musical, and religious change, never mind or dare one say, taste. Which in many ways explains its attraction for Morningside Opera, who see their role as boundary-pushers wishing to invigorate dialogue between traditional and new modes of the form. Their stripped down presentation was both scholastically dense as well as visually provocative.

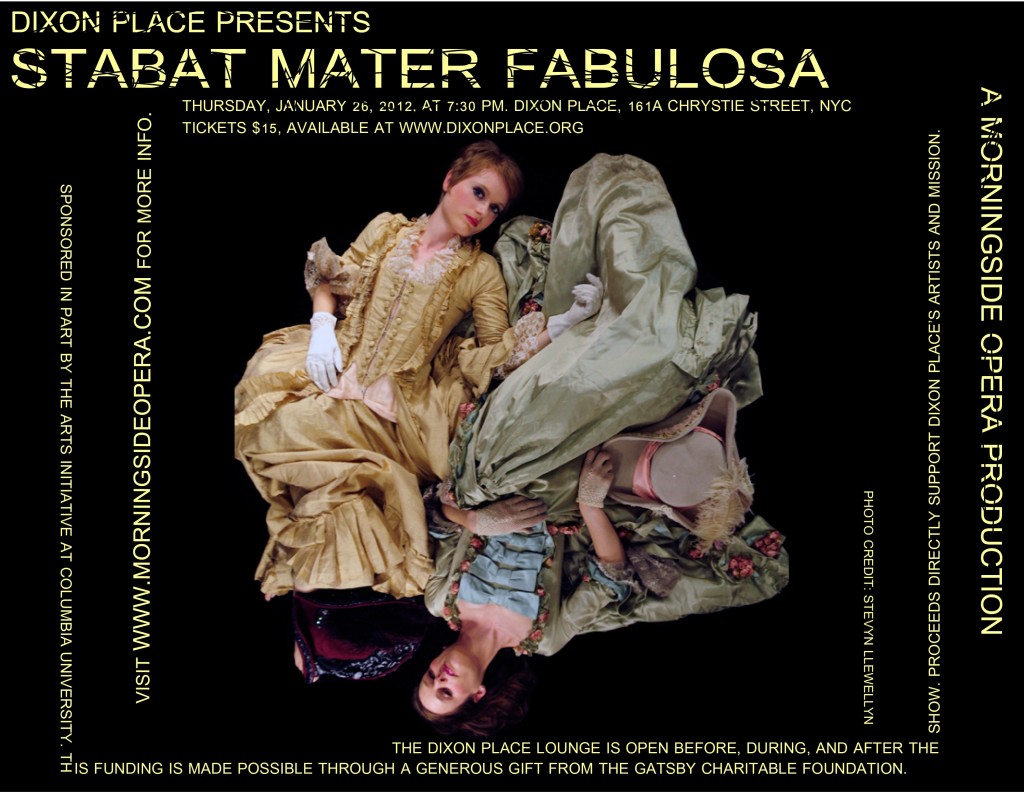

As the slowly drawn out, deliciously mournful harmonies swelled to fill the auditorium, we were presented with two female singers attired in silky camisoles and nickers more evocative of the flapper era than anything from the 18th century. This anachronistic note is key, as the physical performance in large measure is characterized by a panotomimed broadness of expression redolent of the 1920s cabaret era, a time that was interested in the exposure, as much as in the celebration of artifice. From there, as the sequence of songs unfolded, we were subjected to a sort of reverse strip tease as the women, an alto and a soprano, episodically dressed themselves in layer after layer of high baroque costume, enacting scenes in varying degrees ridiculous, mocking, sentimental, and titillating. These little mimes were intentionally played to undermine the exquisite feeling in the vocalizations and critique the psychological realism on display. While this is going on photographic projections were thrown up on a wall behind, exhibiting scenes of feminine intimacy and maternal ideality, a foil to the silly capering and posturing in the foreground. As the singers graduated into foundation garments, dresses, and eventually wigs, the greater question of the construct of feminine identity surfaced and, with a grand historical sweep, addressed details of formal 18th century attire and contemporary notions of the ”undressed” feminine, maternal self. It could not be ignored that the photographs appeared in the form of “projections”, and with some subtle lighting play, remained gauzily vague, fading in and out of prominence.

The voices meantime, ever beautifully harmonized, persisted throughout, hardly impacted by the movements and gestures of the singers as, gamefully, and with dumb show agony, they were trussed into punitive corsets, chased each other about the grand piano, swooned in affected attitudes of grieving faints, and skipped in merry passes, revealing the schism between form and feeling. Implicit is the Roman church’s sado-masochistic excitement at the representation of Mary, mother of Jesus, in her moment of anguished grief, as the vessel of mortification and sorrow that believers should aspire to in contemplation of Christ’s ultimate and bloody sacrifice. That this idea should be elaborated in such a musically sensuous, celebratory style singularly at odds with its subject, is one of civilization’s exquisite, yet abundant paradoxes, and the primary focus of the Fabulosa production. The sense of contradiction is echoed in finer details throughout the performance and is given special focus in the costuming, which plays a central role. One singer is laced tightly into a corset severely compressing the waist, and the other is obliged to saddle herself with a steel-framed pannier belt, which works to dramatically expand the hipline. They both put on identical, pastel colored dresses and harmonize perfectly. Their lofty, powdered wigs are adorned with miniature bird cages, inside of which are tiny birds; the spirit of freedom and movement is entrapped and stilled for human contemplation. The puritanical mindset might demur, but the baroque era is nothing if not anathema to such a sensibility.

The voices meantime, ever beautifully harmonized, persisted throughout, hardly impacted by the movements and gestures of the singers as, gamefully, and with dumb show agony, they were trussed into punitive corsets, chased each other about the grand piano, swooned in affected attitudes of grieving faints, and skipped in merry passes, revealing the schism between form and feeling. Implicit is the Roman church’s sado-masochistic excitement at the representation of Mary, mother of Jesus, in her moment of anguished grief, as the vessel of mortification and sorrow that believers should aspire to in contemplation of Christ’s ultimate and bloody sacrifice. That this idea should be elaborated in such a musically sensuous, celebratory style singularly at odds with its subject, is one of civilization’s exquisite, yet abundant paradoxes, and the primary focus of the Fabulosa production. The sense of contradiction is echoed in finer details throughout the performance and is given special focus in the costuming, which plays a central role. One singer is laced tightly into a corset severely compressing the waist, and the other is obliged to saddle herself with a steel-framed pannier belt, which works to dramatically expand the hipline. They both put on identical, pastel colored dresses and harmonize perfectly. Their lofty, powdered wigs are adorned with miniature bird cages, inside of which are tiny birds; the spirit of freedom and movement is entrapped and stilled for human contemplation. The puritanical mindset might demur, but the baroque era is nothing if not anathema to such a sensibility.

Stabat Mater Fabulosa itself is a rich confection for contemplation. I couldn’t begin to pretend I had understood or unpacked all the pointed charades and features on show. Of course there will be purists (as opposed to puritans) who will not countenance this kind of aggressive deconstruction of a classic that, in some measure, still owns a religious dimension. But that would be their loss. This is a show that could prove as poised on a Las Vegas stage as it might at La Scala. One scene, where the scantily clad singers, supine together atop the grand piano, draw on stockinged hose while intoning Latin lines of dolorous gravity – “O how sad and afflicted was that blessed mother of the only- begotten” – could write its own ticket to play anywhere. Well, almost anywhere. And that alone, perhaps, might suffice as a badge of success.

Brett Umlauf and Amber Youell were respectively the soprano and alto performers and displayed a real harmonizing intimacy in their singing, despite all the distractions they had to attend to. Kelly Savage was the stalwart keyboard accompanist, and Laura Careless devised choreography and movement. The projections were supplied by Jessica Ng, and the utterly thoughtful and no less fabulous costumes were the work of Annie Holt. One would hope and think that this production was on the radar of the opera community, and that it should stimulate the sort of discussion and investigation that Morningside Opera aspire to provoke. For all its playful heart, Stabat Mater Fabulosa ultimately proves perfectly serious.

~~~

For more information about Morningside Opera please visit their site and join them on Facebook.

{ 0 comments… add one now }